UX Brighton 2022 - 4th November

Just to warn you now, this is basically an essay

The brilliant return of UX Brighton

UX Brighton, a mainstay of the Brighton UX community returned on 4th of November after a 2-year hiatus. This year’s event focused on UX and Product Management. I have been reflecting on this intersection both personally and professionally of late and outline my thoughts below. Some thoughts are fledgling, some are fully formed, some I may revisit, some I may abandon later.

The level of a problem

Products solve customer’s problems or as I prefer to term it products provide a means for customers to get the thing that they want to do, done (props to Christensen et al. as this is blatantly inspired by Jobs-to-be-Done). So a product should represent an innovation in that it makes that thing they want to do quicker, or easier, or safer, or cheaper, or some combination of the former. But what about once that product exists? It needs to mature and respond to the way the customers change, their contexts change, or the thing that they are trying to do change. These are internal problems for the product to address within itself so that it might carry on solving the high-level problem for the most customers and also gain new customers.

When a product stops solving a problem

I am in the process of moving away from Evernote. As a committed customer for many years it used to be my brain outside my brain. Was it the lack of new features that pushed me away? No, although I am intrigued by the promise of transclusion and interconnection between thoughts and ideas, I was still mostly happy with it. Ultimately, what pushed me away were the little cracks in functionality; the five times duplicated note, the slow load times, the indexing failures. My trust was broken, just like an unreliable human relationship it was the little things which set off alarm bells. As a seasoned technologist, these tell-tale signs of an unloved product get me packing my bags. To the point where my bags are packed before I’ll even adopt a product these days (shakes head at proprietary file formats). No escape plan, no deal. This is what comes from years of being the person charged with saving other people’s data.

Defining a problem

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say defining the definition of a product-problem. In UX a problem might be at a micro level as in a specific process or interaction is failing, e.g., I cannot buy the replacement fridge-freezer I need due to an issue with one part of the payment workflow on a popular UK-based vendor’s website (true story). At a product level, if that website were a product and it’s primary purpose was to enable the successful sale of fridges then that product has failed. So UX problems can be product problems. So, is it more about the lens by which we see these problems? Could it be that the product manager owns a collection of problems across the product’s development cycle and the UXer owns their problems as a subset of that. I think that is how I interpret it as someone outside that particular domain, yet also identifying with it. My products are learning experiences, when they are successful they result in the subsequent adoption of desired behaviours. If the means of product delivery in terms of suitability, usability, accessibility, availability, reliability, and robustness fails, then my product also fails.

Defining a collection of problems

Problems do not exist in a vacuum and are often symptomatic of bigger issues. So, acknowledging the breadth and distribution of problems and then identifying which are the most important and impactful to address is essential. This theme arose in both Janna Bastow’s and Matt LeMay’s talks. Deciding what is most important relies on research and analysis based on having access to a variety of information sources.

It is also clear that a collection of problems derive from and are influenced by multiple domains within a business. So this is where the connections between business strategy, product strategy, and UX strategy converge. Jaime Levy’s excellent book on UX Strategy was referenced by speaker, Alison Rawlings. A profoundly influential book during my years in graduate school. This was where I learned about business research staples such as competitor analyses, a method I still use frequently today.

How did someone else solve this problem? Was the outcome a new product, or a collection of approaches working alongside a product (more like a service)?

Defining plans to address each problem in your collection

This is where it all gets a bit Pokemon, but then consider for a moment an epic boss-style battle in Pokemon or any other strategy-based game. You have a collection of problems; your opponents, the posse of pokémon. You have a bunch of constraints; the skills that your pokémon have, and those skills in comparison to your opponent’s skills. Your battle strategy should reflect that nuance of playing to the strengths of your pokémon or the weaknesses of your opponent’s pokémon. There is probably a reason why the word strategy conjures up pictures in my mind of mustachioed people in a room playing a gigantic game of Risk. It is complex, it is messy, and very few people have a holistic viewpoint, preferring to stick to their own area of the board. Then add to all of this chance and the inevitable risk that brings; the roll of the dice, the rogue influence of a powerful person, a pandemic.

Defining a strategy as a collection of plans

A strategy attempts to understand problems, barriers, constraints, context and external influencing factors and create a framework for plans, and by extension a rationale for decisions. As Matt LeMay noted, your goals will gain clarity if you can explain the reasons for trade-offs.

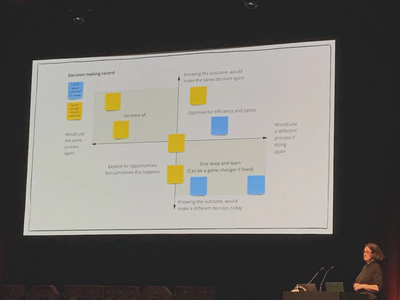

Making decisions and actioning plans

To expand on the above further, I feel that strategy can be a framework or container for plans, plans are the catalyst for actions, and actions are reliant on decisions. So my key take away from speakers Lucy Spence and Alison Rawlings was the need for clarity in decision making. Good decisions, or at least a decision of best-fit, are research and data informed. Decisions should also be reflected upon after they are made. As an approach to this Spence shared statements that she uses to bring transparency to her decision making:

-

Knowing the outcome, I would make the same decision again

-

Knowing the outcome, I would make a different decision today

-

I would use the same process to solve the problem again

-

I would use a different process if I were doing this again

My decision to use Evernote back in 2013

Let’s take a look at decision to adopt the Evernote product in the first place, perhaps I will gain further clarity…

Selected statement:

Knowing the outcome, I would make a different decision today

Why?

Because my expectations have shifted and I have changed since I adopted Evernote. It is also proving to be quite a lengthy process to get my notes out intact1.

How have you changed?

Well, I’m much more into coding than I was back in 2013. I suppose I want a note taking app a bit more like GitHub with tagging and version control.

It sounds like the context has changed…

My expectations have changed because the technology landscape has changed. But my skills and knowledge in coding were the catalyst for my increased awareness of the broader technology landscape.

Selected statement:

I would use a different process if I were doing this again.

Why?

Because my requirements have changed. The issues with functionality have probably just pushed the matter forward.

A ha! There we are getting to the truth of the issue, but like any human decision it isn’t clear cut. I had outgrown the product and my trust was degraded, the combination of both led to a level of inconvenience so as to hasten my move.

Recognising when your plans are not working and correcting the course

As noted by speaker Janna Bastow, this might manifest as solving too many problems for a small number of influential people, at the expense of solving the biggest problems for the most people. Bastow advocated splitting up this kind of custom or agency-style work from the product work. This is an interesting idea as it is clear to me throughout my career that large scale projects have often suffered at the expense of the small ones. While many small projects which seem doable on paper, ultimately they eat up the time which should be dedicated to larger ones. Lest us not forgot that having many smaller projects on the go calls for the need to routinely context-switch which consumes more mental energy as a matter of course. The popularity of methods such as Sprints, indicate this need for placemaking for mental space-making.

To conclude

To conclude, it is clear to me that when you own a product, it is always on show. What I mean by that is that as long as a product fulfills the core need then it will be loved and largely ignored, but when the cracks appear and that situation is compounded by eager competitors or lack of innovation then abandonment feels more enticing. I always had respect for product managers, now I have even more.

Random closing thought

Was Captain Kirk engaging in metacognition when he took the Kobayashi Maru test? If you take the scenario at face value he cheated at the test. However, was Kirk considering this problem-space of the Kobayashi Maru at a philosophical level? Kirk refused to accept that the solution was predetermined and by researching the situation found an alternative. This alternative reflected his personal ethos and values. These values persisted throughout his career, he did not accept the no-win scenario2. There was always a solution, he just needed the right crew of people to work together and see it.

This reminds me of two of my favourite points in Matt LeMay’s talk…

“Most questions of role clarity are actually best resolved by goal clarity…” “High performing cross-functional teams naturally self-organise around shared goals.”

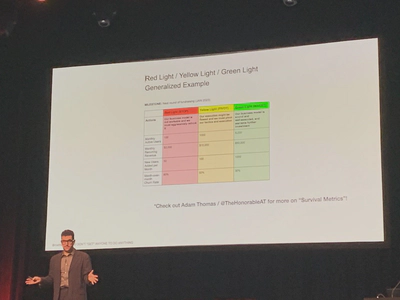

LeMay also provided a great primer on Adam Thomas’ (@TheHonorableAT on twitter) ‘Survival Metrics’ which relate to the sunk cost fallacy (which Mr Spock explains below).

-

If you are interested, I have moved to Obsidian and used the following script to convert my notebooks to Markdown: GitHub - Aias/evernote-to-markdown: Converts HTML notes exported from Evernote to plain markdown files, to do with what you will. On that point I also write this blog in Markdown; a clear example of how my requirements have changed since 2013. ↩︎

-

Of course [spoiler alert] Khan put Kirk’s ethos to the test (in both the original and the reboot), but that could be a whole other blog post. ↩︎